Colorado

Carbondale

Marble

Marble is a tiny town tucked high in the Crystal River Valley, a forgotten seam in Colorado’s rugged fabric that once yielded some of the purest, most sought-after stone on Earth. This speck of a town helped carve the national identity—literally. The marble that lines the Lincoln Memorial was cut and pulled from these very mountains, 9,300 feet above sea level.

Massive blocks, some weighing over a hundred tons, were cut using high-pressure water, hand drills, and dynamite. Narrow-gauge rail lines clung to the mountain like veins, carrying the blocks down to the valley floor and eventually onto a standard rail line that connected to the rest of the country.

Though nature is slowly reclaiming the site, the bones of the old mill are still visible. Walking through what was once the largest marble finishing mill in the world, it’s not hard to imagine the past. The mill once sprawled across five acres, filled with gang saws and polishers that brought raw blocks to a gleaming finish. Run by workers lodged in cramped, wood-framed bunkhouses that groaned in the winter winds working long and dangerous days. In the cold months, snow piled waist-deep, and inside the mill, marble dust coated everything. They said the air was so thick with it, it looked like a foggy night in London. Evenings meant whiskey, cigarettes, harmonicas. Fights weren't sent to some fat HR lady with a double chin and stinky armpits but rather settled right then and there, amongst the marble colosseum.

Now lay huge rectangular slabs amidst the mill with random pillars reaching for the open sky. The skeleton of the main building still remains, open to the weather and whatever else finds itself amongst its bones. I ran my hand along the weathered edge of a slab, no longer a precise 90° edge, cool, impossibly smooth, like touching the belly of a glacier. Even in ruin, there was a lingering sense of magic, of good old fashioned hard work. A knowing that at one point, marble was.

Oh but the irony. The very town that helped create America’s most enduring monuments could not endure itself. The Great Depression hit hard. Foreign marble undercut prices, wars, and the unpredictability and cost of high-altitude transport all helped slow the heartbeat of Marble. The mill shuttered. The town emptied. Yet, the stone remains.

Paonia

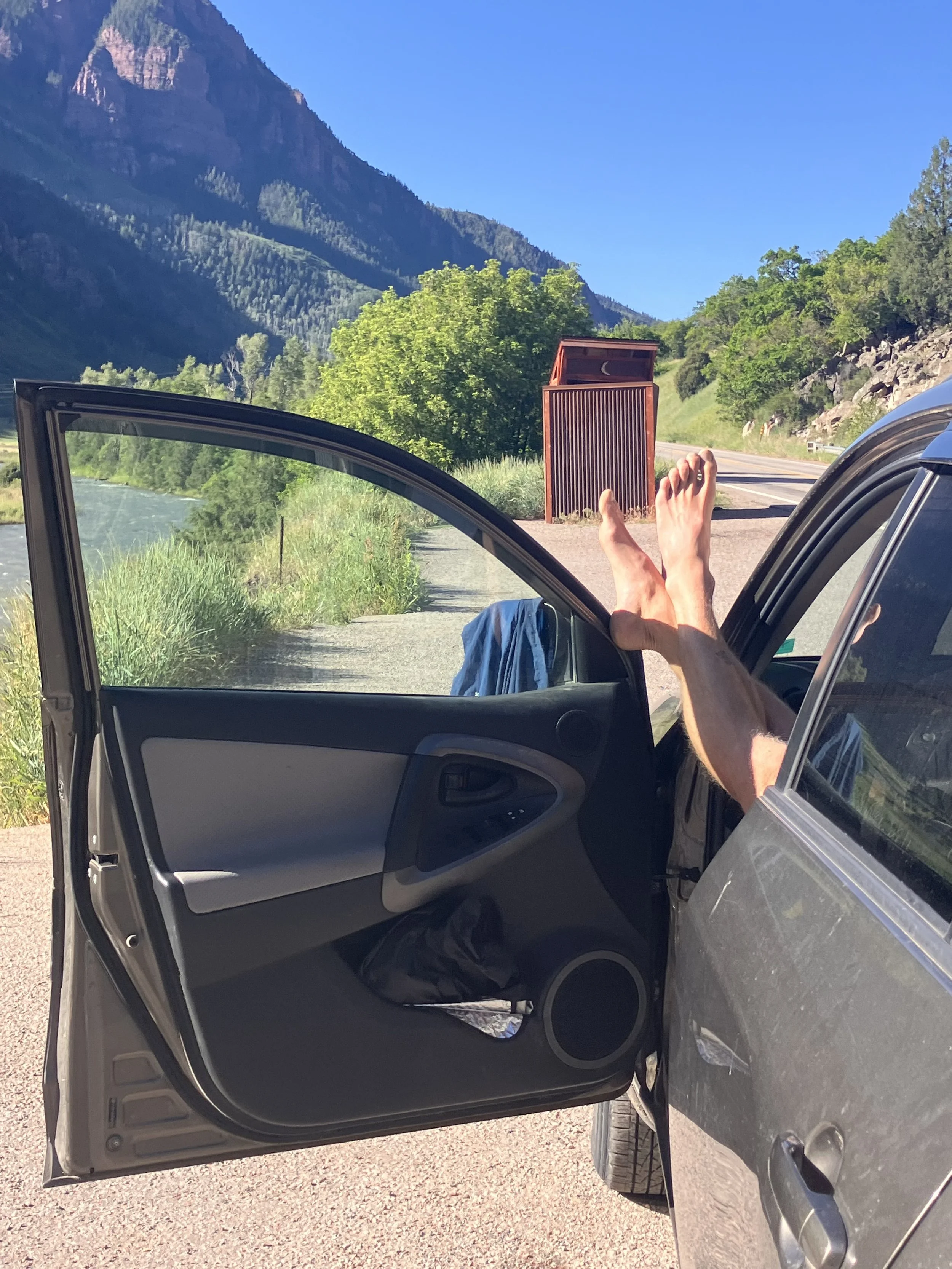

We rolled into Paonia from the north and yet again, it was hot as balls. After winding our way off Highway 133, the Paonia River Park was one of the first places we hit, less out of planning but rather to cool off with a dip in the North Fork Gunnison River. What was thought to be just a quick dip turned into an unexpected delight when we saw this humble little park wasn’t just a spot to cool off, it was also an open-air art gallery featuring metal sculptures.

Scattered along railings and tucked beside pathways were steel creatures: ants marching in formation, cranes caught mid-stride, beavers frozen mid-chew. Piece after piece, each teeming with tiny, intricate metal detail and hidden behind or beneath the railings to boot, quietly existing whether seen or not. And just when you thought you’d seen it all, you’d take another step and spot the next. The sheer quantity of quality work. I knew this wasn't just some random person fabricating these, there was no way. I looked up the genius behind the welding torch and found they were made by local blacksmith, Ira Houseweart. A two-time winner of the History Channel’s Forged in Fire, a master metalworker who bridges old-world forging with modern design. His functional pieces, railings, gates, and custom metalwork, integrated with expression, all cut from the same cloth of integrity and care. My energy shifted to a higher frequency knowing that there are people like Ira are out here doing their thing.

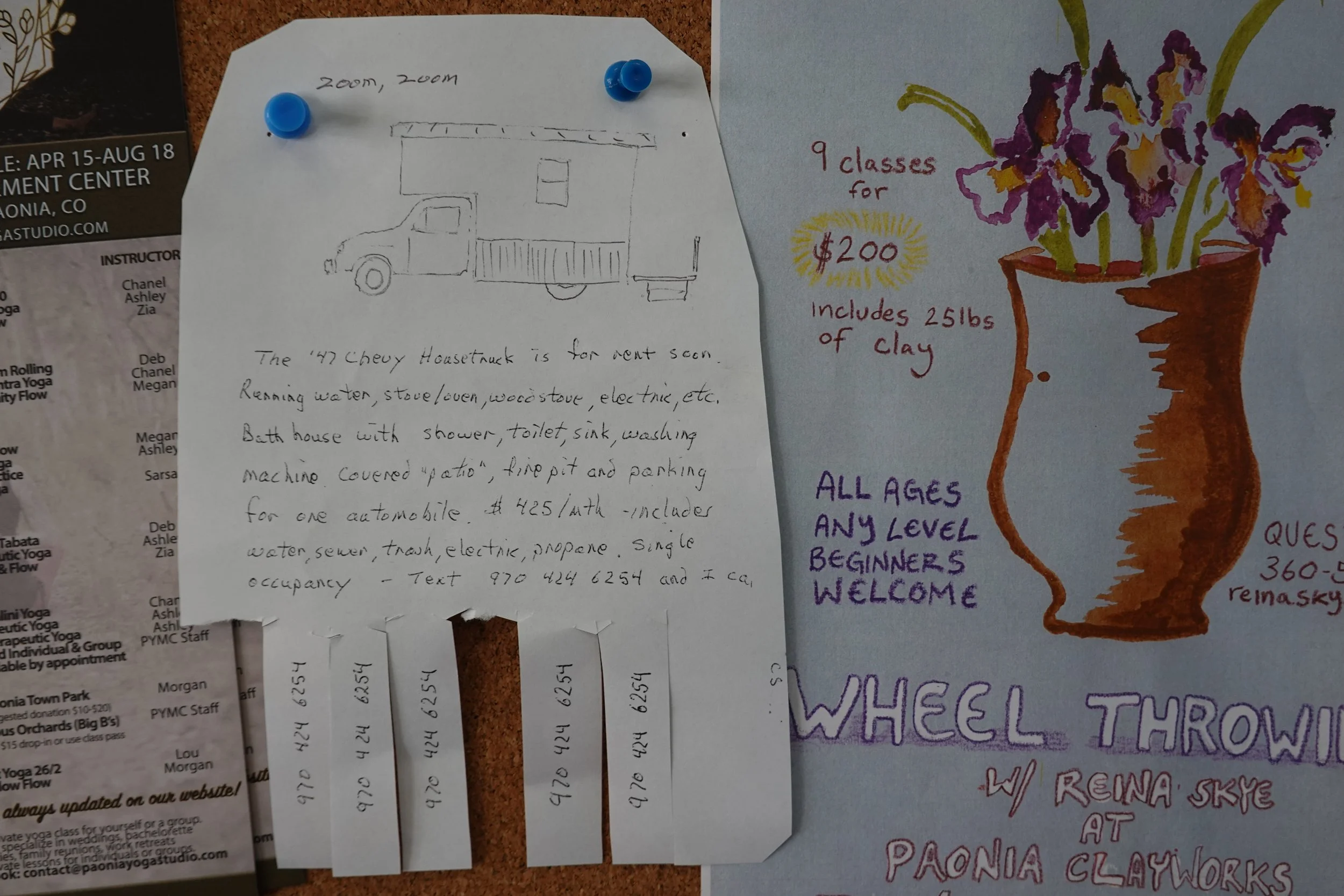

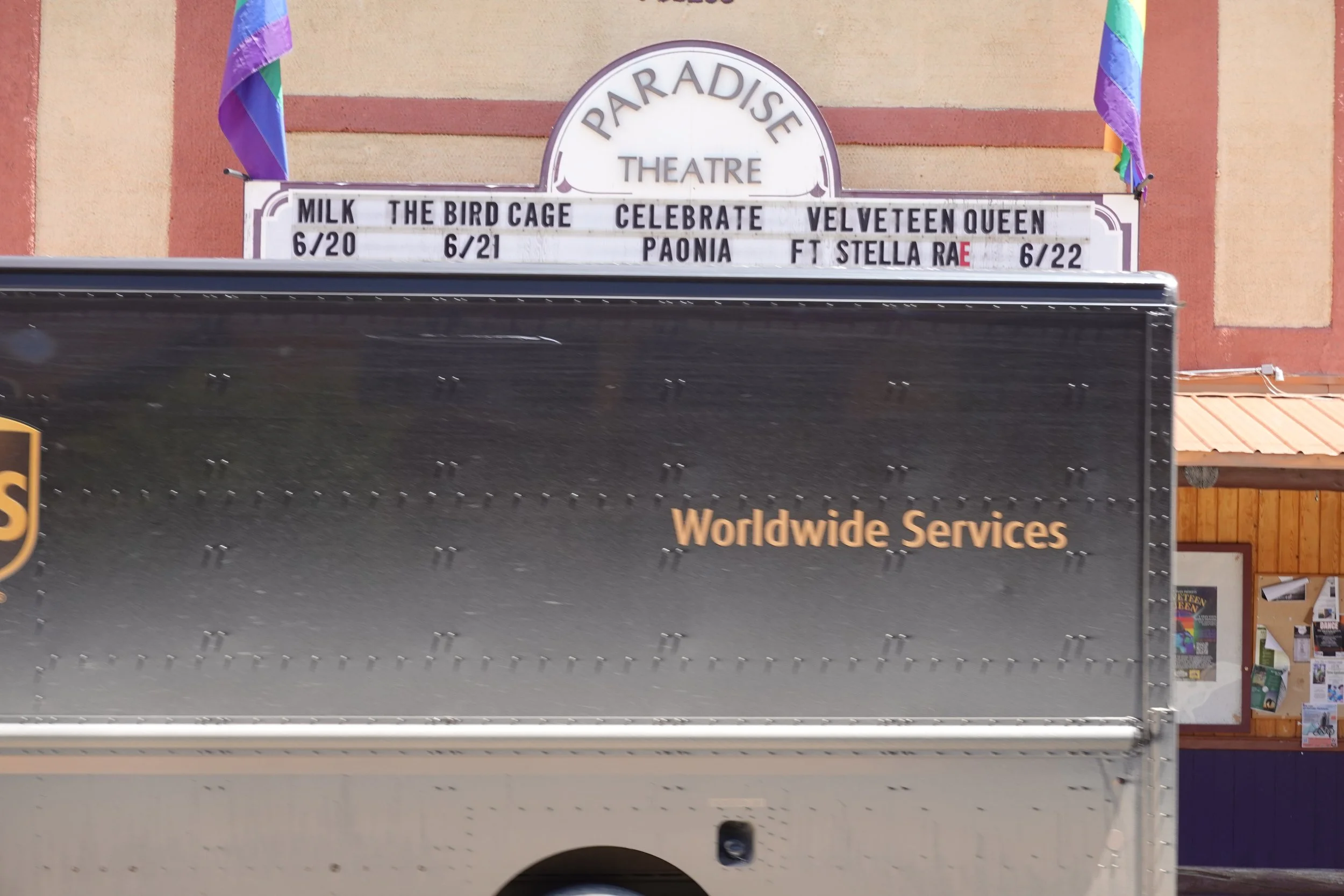

But the magic of Paonia isn’t limited to the park. We found Paonia to be filled with creative energy. Murals peeked out from alleyways. Tiny galleries hide behind garden fences. There’s art tucked into corners you’d never think to look. From bakeries to bulletin boards in an organic grocery store, where i spotted a handwritten ad for a truck for sale. You just don't see that type of thing anymore.

Paonia isn’t just an artist’s dream, it’s also a farmer’s playground. The North Fork Valley’s soil is dark, rich and nutrient-rich. The land here in notorious for its peaches, apples, cherries, plums. There are also dozens of small-scale farms where growers take their crops and methods to the edge of imagination and down the rabbit hole of “what if”.

The town’s roots go deep. Founded in 1881 by Civil War veteran Samuel Wade, Paonia got its name as a spin on “peony,” the flower he grew here. What started as a mining and agriculture town has evolved into a sanctuary for artists, off-grid dreamers, and anyone looking for a slower, richer way to live, perhaps even a slice of how the world could be.

After exploring the town, we rolled back onto Hwy 133 and not long after stumbled into Big B’s Delicious Orchards. A cider house/campground/place to drink a cold cider and let your brain go slack in the sun. The whole backyard is lined with wood chips, a small stage set patiently awaiting local musicians. Huge adult-sized rope swings hang from beams with a sign reading something along the lines of “use at your own risk”. Giant Jenga. Giant Legos.